The Artemis program was supposed to mark a triumphant return of American astronauts to the Moon. Instead, it has become a case study in delays, technical failures, ballooning costs, and uncomfortable honesty from NASA leadership itself. After the latest wet dress rehearsal failure, Artemis 2 has been delayed yet again, and for the first time, a sitting NASA administrator publicly acknowledged what critics have argued for years: the Space Launch System (SLS) is deeply flawed.

In a rare moment of candor, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman described SLS as “one of the worst vehicles the agency has ever operated.” That statement alone sent shockwaves through the aerospace community. But the real story lies deeper—in hydrogen leaks NASA solved decades ago, a rocket that flies once every few years, and a system that costs billions per launch.

Let’s break down why SLS keeps failing, why NASA can’t seem to fix it this time, and why SpaceX’s Starship increasingly looks like the future—despite its own challenges.

Artemis 2 Delayed Again: A Rocket Nobody Trusts

The Artemis 2 mission, which will send astronauts around the Moon for the first time since Apollo, has now slipped to no earlier than March 2026. On paper, that gives NASA an extra month to prepare. In reality, it does very little to inspire confidence.

This is a rocket that has already consumed more than $20 billion, yet continues to fail in eerily familiar ways. Hydrogen leaks, a problem NASA mastered during the Space Shuttle era, continue to plague SLS despite years of testing and redesign.

Anyone strapped atop a vehicle with a four-year history of unresolved cryogenic leaks has every reason to be nervous.

Why Hydrogen Leaks Keep Happening

Component Testing vs. Reality

During a February 3rd, 2026 press conference, John Honeycutt, Artemis 2 mission manager, explained NASA’s reasoning. According to him, every individual component of SLS is thoroughly tested—but the launch environment cannot be perfectly recreated on the ground.

Liquid hydrogen operates at extreme cryogenic temperatures, and its molecules are tiny, fast-moving, and relentless. Even microscopic imperfections—too small to detect in component-level testing—can become major leaks during actual tanking.

In simple terms:

Everything works… until it’s all assembled and fueled for real.

The Rollout Problem

Amit Kshatriya, NASA’s Moon to Mars program manager, highlighted another contributor: the rollout itself.

Moving a rocket weighing millions of pounds from the Vehicle Assembly Building to the launch pad introduces:

- Vibrations

- Accelerations

- Structural stress

These forces can subtly shift ultra-precise seals by fractions of a millimeter—enough to let hydrogen escape. The problem is compounded by the fact that NASA cannot fully measure or predict these effects.

And then comes the most uncomfortable truth of all.

Every SLS Rocket Is Basically a Snowflake

No two SLS core stages are identical.

Each rocket is hand-built, with slight variations in manufacturing, alignment, and tolerances. That means a fix that works on one SLS does not guarantee success on the next.

This is the opposite of modern rocket design philosophy—and it has serious consequences for reliability.

NASA Has Solved This Before—So What Changed?

To understand why NASA’s explanation feels unsatisfying, we need to rewind to 1990.

The Space Shuttle’s “Summer of Hydrogen”

During the STS-35 mission, Space Shuttle Columbia was delayed for more than three months due to persistent hydrogen leaks at a critical interface.

NASA’s response was swift and uncompromising.

Enter the Tiger Team

A dedicated Tiger Team, led by engineer Bob Schwinger, was formed with a blunt mandate:

“Don’t go back to Huntsville until this is fixed.”

The team conducted:

- Full fault-tree analysis

- Cross-center collaboration

- Retorquing of bolts

- Replacement of suspect components

- Removal of microscopic glass beads from prior refurbishments

After multiple tanking tests, the result was clear.

On October 30, 1990, Columbia was declared the tightest, most leak-free orbiter NASA had ever flown.

The fix cost $3.8 million—and it worked.

How NASA Mastered Hydrogen Leaks

Throughout the Shuttle era, NASA repeatedly encountered hydrogen leaks at the Ground Umbilical Carrier Plate (GUCP). But each time:

- The root cause was identified

- Seals were replaced

- Interfaces were realigned

- Additional tanking tests were conducted

By 2011, hydrogen leaks had virtually disappeared.

Not because hydrogen changed—but because NASA gained experience.

The Space Shuttle flew 135 missions, giving engineers hundreds of real-world fueling cycles to learn from.

SLS Has the Opposite Problem

A Rocket That Barely Flies

SLS flew Artemis 1 in late 2022.

It won’t fly Artemis 2 until 2026.

That’s more than three years between launches.

Even looking ahead, SLS is expected to launch once every one to two years—at best.

According to Jared Isaacman, this is the elephant in the room.

Jared Isaacman’s Brutally Honest Admission

Responding to an analysis by space journalist Eric Berger, Isaacman didn’t deflect or spin.

He wrote:

“The flight rate is the lowest of any NASA-designed vehicle, and that should be a topic of discussion.”

Unlike Saturn V or the Space Shuttle—both designed for far higher launch cadences—SLS was never built to scale.

With such long gaps between launches:

- Every wet dress rehearsal becomes an experiment

- Every fueling operation feels like a first attempt

- Problems never get “rung out” through repetition

Why Wet Dress Rehearsals Keep Failing

NASA conducts exhaustive:

- Wet Dress Rehearsals

- Pre-Flight Readiness Reviews

- Flight Readiness Reviews

Not because they’re overly cautious—but because they know SLS will break.

With years between flights, cryogenic systems never reach operational maturity. Every rollout reintroduces:

- Thermal stress

- Vibration effects

- Seal alignment uncertainties

- Ground system quirks

This is why hydrogen leaks keep coming back.

“Not the Forever Rocket”

Isaacman went even further.

He openly stated that SLS is not the most economical path—and certainly not the forever path.

Many of its problems stem directly from its Space Shuttle heritage, including:

- Complex cryogenic plumbing

- High operational costs

- Infrastructure that can’t scale

- Extremely low flight rates

Yet, despite all of that, NASA still defends SLS.

Why NASA Still Needs SLS—For Now

Here’s where the argument gets complicated.

Despite its flaws, SLS is currently the fastest path to returning American astronauts to the Moon—at least through Artemis 5.

Geopolitics Matter

With China accelerating its lunar ambitions, the U.S. needs:

- A heavy-lift rocket that exists today

- A system capable of launching crews without orbital refueling

- Maximum safety margins for first-time deep space missions

SLS delivers that—at an enormous cost.

The Most Powerful Rocket NASA Has Ever Operated

In its Block 1 configuration, SLS produces:

- 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff

That’s more than Saturn V.

But power comes at a staggering price.

The True Cost of SLS

Development Costs

- Over $29 billion by 2024–2025

- $35.4 billion when adjusted for inflation

Cost Per Launch

- NASA estimate: $2–2.5 billion

- Inspector General & GAO estimate: Closer to $4 billion per launch

This makes SLS the most expensive rocket in history—by far.

Why Artemis 3 Depends on SLS

For Artemis 3, SLS remains essential.

It is currently the only rocket capable of:

- Launching Orion

- Carrying four astronauts

- Meeting NASA’s stringent human-rating requirements

- Injecting the spacecraft directly into trans-lunar orbit

No commercial rocket can do this today—not even Starship—without additional unproven steps.

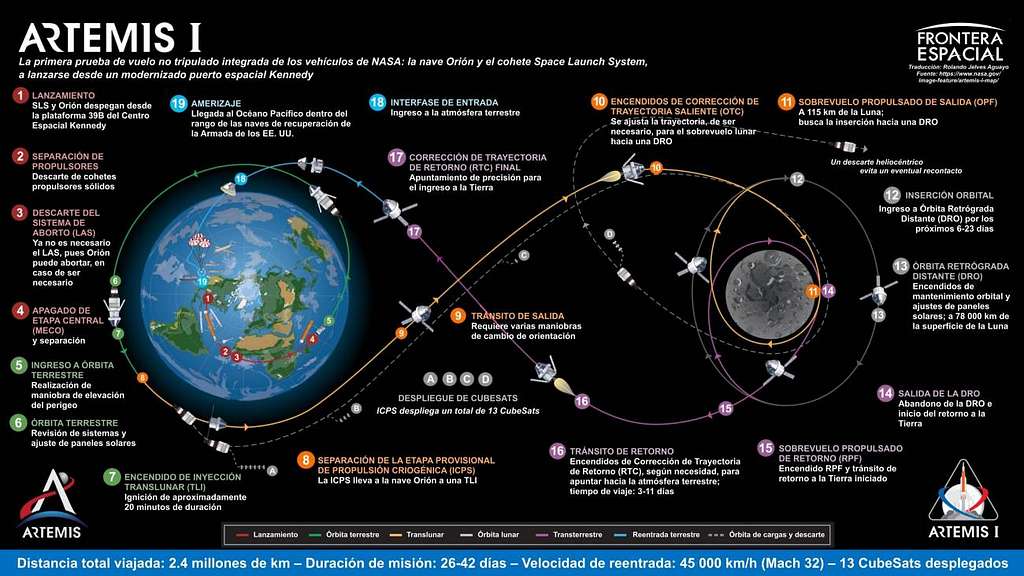

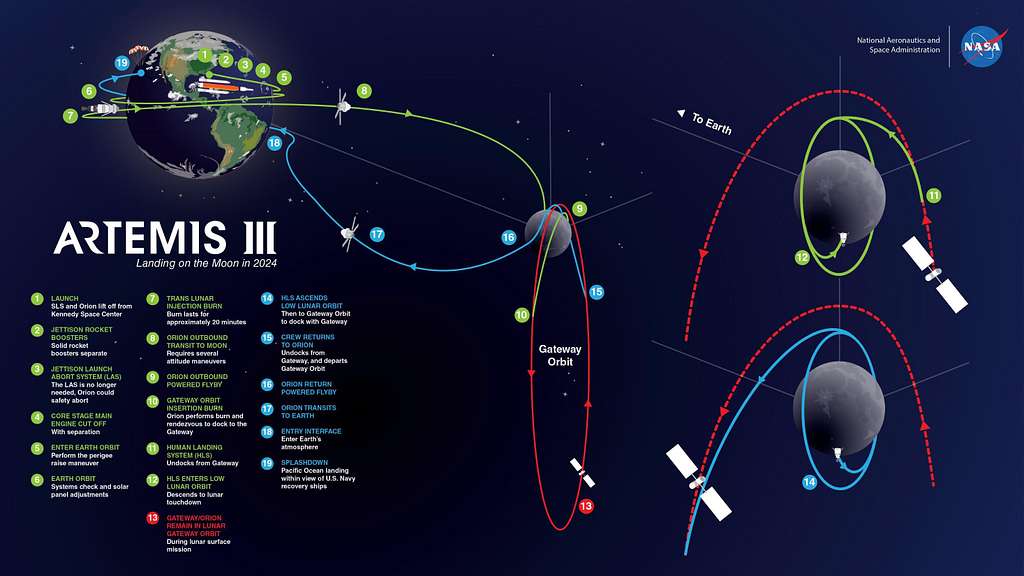

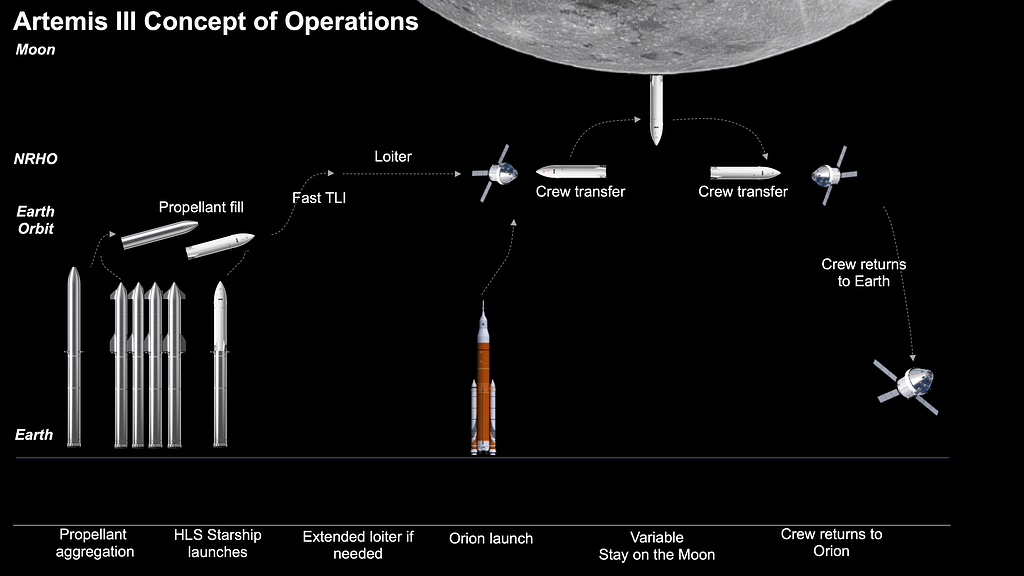

How Artemis 3 Will Work

- SLS launches Orion and four astronauts

- Orion enters lunar orbit

- Orion docks with SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System

- Two astronauts descend to the lunar south pole

- Roughly one week of surface operations

- Astronauts return to Orion

- Crew heads back to Earth

This hybrid approach is why NASA still calls SLS the fastest path back to the Moon.

Why Artemis 2 Is So Critical

Before any of that can happen, Artemis 2 must succeed.

The mission will:

- Send astronauts around the Moon

- Test Orion’s life support systems

- Validate deep-space operations

- Survive record-breaking reentry speeds

Without Artemis 2, Artemis 3 is dead on arrival.

SLS vs. Starship: The Real Divide

SLS offers:

- Simplicity

- Direct trajectories

- Massive safety margins

Starship promises:

- Reusability

- Rapid iteration

- Drastically lower costs

- High launch cadence

The irony?

NASA trusts Starship to land astronauts—but not yet to launch them from Earth.

Final Thoughts: Disaster or Necessary Evil?

SLS is:

- Slow

- Unbelievably expensive

- Technically fragile

- Operationally outdated

And yet, for now, it remains NASA’s best option for near-term lunar missions.

Jared Isaacman’s honesty signals a turning point. NASA knows SLS is not sustainable. The future belongs to high-cadence, reusable systems like SpaceX Starship.

But until those systems are fully proven for crewed missions, SLS—disaster or not—remains the bridge back to the Moon.

The real question is not whether SLS will be replaced.

It’s how long NASA can afford to keep flying it. 🚀

FAQs

1. Why did NASA delay the Artemis 2 mission again?

NASA delayed Artemis 2 due to persistent hydrogen leaks discovered during the wet dress rehearsal. These leaks pose safety risks and must be fully resolved before astronauts can fly.

2. What is the main problem with NASA’s SLS rocket?

The biggest issue with SLS (Space Launch System) is its chronic hydrogen leakage, extremely low launch cadence, and high operational complexity, which prevent problems from being permanently fixed.

3. Why are hydrogen leaks so hard to fix on SLS?

Liquid hydrogen molecules are extremely small and mobile. When combined with ultra-cold temperatures, rollout vibrations, and custom-built hardware, even microscopic gaps can cause leaks that are difficult to detect during ground testing.

4. Didn’t NASA solve hydrogen leak problems during the Space Shuttle era?

Yes. During the Space Shuttle program, NASA successfully identified and eliminated hydrogen leaks through high flight rates, repeated tanking cycles, and systematic root-cause analysis—something SLS lacks.

5. How often does the SLS rocket launch?

SLS is expected to launch once every 1 to 2 years, making it the lowest flight-rate rocket NASA has ever operated, according to NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman.

6. Why is a low launch cadence a serious problem?

A low launch rate means less operational experience, fewer opportunities to refine systems, and higher risk that known issues will reappear with each mission.

7. How much has NASA spent on the SLS program?

NASA has spent over $29 billion on SLS development alone. When adjusted for inflation, total costs exceed $35 billion, making it the most expensive rocket program in history.

8. How much does each SLS launch cost?

While NASA estimates $2–2.5 billion per launch, independent analyses from the GAO and NASA’s Office of Inspector General place the true cost closer to $4 billion per mission.

9. Why does NASA keep using SLS despite its problems?

NASA continues to use SLS because it is currently the only rocket capable of launching the Orion spacecraft and astronauts directly to the Moon in a single flight with maximum safety margins.

10. Is SLS better than SpaceX Starship?

SLS is more conservative and safety-focused, while SpaceX Starship is cheaper, reusable, and designed for rapid launches. Long-term, Starship is considered the more sustainable option.

11. Why can’t Starship replace SLS right now?

Starship still requires in-orbit refueling and assembly, which have not yet been proven safe for crewed lunar missions, making SLS the safer short-term option.

12. What did NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman say about SLS?

Jared Isaacman stated that SLS has the lowest flight rate of any NASA vehicle and acknowledged it is not the most economical or long-term solution for lunar exploration.

13. What is the role of SLS in Artemis 3?

SLS will launch the Orion spacecraft and four astronauts into lunar orbit, where Orion will dock with SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System.

14. What happens if Artemis 2 fails?

If Artemis 2 fails, NASA cannot proceed with Artemis 3, delaying the first crewed lunar landing and potentially jeopardizing U.S. leadership in space exploration.

15. Is SLS NASA’s “forever rocket”?

No. NASA leadership has openly stated that SLS is not a long-term solution. It is considered a temporary bridge until reusable systems like Starship are fully operational for human spaceflight.

Read More:

- Something Weird is Happening At Tesla

- Tesla engineers deflected calls from this tech giant’s now-defunct EV project

- IT’S HERE! New Tesla MODEL 2 2026 Senior Edition! 48V + Octovalve + gigacasting, used cars crash

- Elon Musk Revealed Breakthrough Goals for Starship V4 & Raptor 4 Stunned the whole Rocket industry

- Tesla to a $100T market cap? Elon Musk’s response may shock you

- Where to Buy Tesla Optimus Robot 2026: Everything You Need to Know